|

|

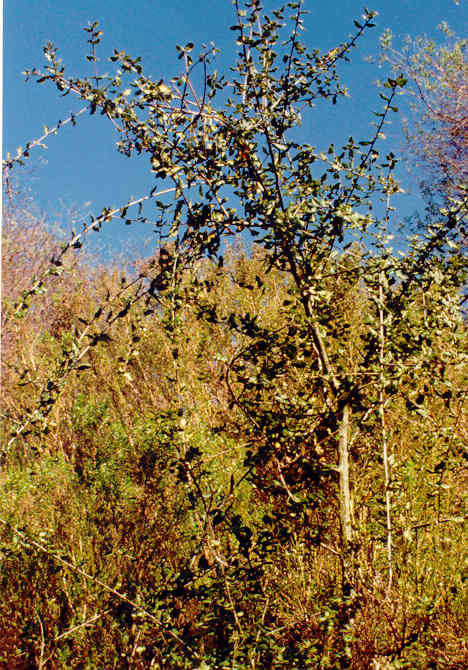

Quercus agrifolia Nee var. agrifoliaFagaceae (Oak Family)NativeCoast Live Oak |

February Photo

Plant Characteristics:

Evergreen tree (6) 10-25 m. tall, top wide; trunk bark becoming furrowed,

widely ridged, checkered, dark gray; lvs. 2.5-6 (9) cm. long; petiole 4-15 mm.,

blade oblong, elliptic, or +/- round, tip rounded to spine toothed, margin

weakly spine toothed, upper surface strongly convex, +/-dull green, glabrous,

lower surface glabrous to sparsely hairy, especially at vein axils, dull, pale

green; trichomes stellate cob-webby, yellowish to grayish, with relatively long

rays, these often intertwined; staminate fls. catkins, 1-several, slender, on

proximal part of twig, 30-60 mm. long, stems hairy; pistillate infl. axillary

among upper lvs., short-stalked, fl. generally one; fruit maturing in one year,

sessile, cup 10-16 mm. wide, 8-15 mm. deep, obconic, scales thin, +/- glabrous,

brownish; nut 25-35 mm. long, 10-14 mm. thick, slender, ovoid, tip pointed,

shell woolly inside.

Habitat and Distribution:

Southern Mendocino Co. south through Coast ranges, western Transverse

Ranges, Peninsular Ranges and along the coast to the western slopes of the

Sierra San Pedro Martir in northwestern Baja Calif., Mexico.

Q. agrifolia var. agrifolia

is widespread in the coastal areas and lower cismontane mountain slopes from San

Bernardino Co. and Ventura Co. east to the southern slope of the San Gabriel

Mtns., Los Angeles Co. and the San Bernardino Mtns., south through Orange Co.,

western Riverside Co., and coastal San Diego Co., to at least the vicinity of

San Vincente in Baja Calif.; Santa

Rosa and Santa Cruz Ids.; sea level to 900 m.

Common in canyons, foothills, valleys and mesic slopes; Southern Oak

Woodland, Sycamore Woodland, and Chaparral.

(Roberts, Oaks of So. Calif

Floristic Province 28).

Name:

Quercus, ancient Latin name for

oak. (Hickman, Ed. 658).

Latin, agri, a field and Latin,

folium, a leaf.

(Jaeger 11, 104). Agrifolia,

foliage of the fields, possibly pertaining to the evergreen oaks of the species

that frequent the valley floors.

General: Rare in the study area with only one tree known and this on the northerly side of big canyon, at the toe of the bluff, about 200 feet off of Back Bay Dr. This tree must be several years old, but was only noticed in 1995 after the Fish and Game cut down a large Myoporum which had grown up in front of it. The shape of the tree has been influenced by the Myoporum as it is tall and scraggly. (my comments). The acorn has long been recognized as one of the outstanding undomesticated food sources of the New World, creating a stable food resource that heavily influenced the socio-cultural development of those societies fortunate enough to possess it. In California, the chief source of food for the Indians was the acorn, an excellent and fairly reliable source of nourishment. It has been suggested that the lack of significant development of aboriginal agriculture in California could be traced to the fact that an agricultural economy in its initial stage would have been less productive than the native economy given an abundant food source such as the acorn. The most important food source of the Cahuilla, Indians of the Colorado Desert, the San Bernardino and San Jacinto Mountains, was the acorn. Four species of oak were used by the Cahuilla, Q. kelloggii, Q. agrifolia, Q. dumosa, and Q. chrysolepis, the most favored being Q. kelloggii, which was said to have outstanding flavor and the most gelatin-like consistency when cooked, a prerequisite for good acorn mush. The mountain groups of Cahuilla had the advantage of possessing the choicest oak groves. Two of their finest oak grove areas were in the Cahuilla Valley near what is now Anza and throughout the area that is today Los Coyotes Indian Reservation. The Cahuilla groups on the Colorado Desert exploited the least favorable acorn-gathering sites. Oak groves were owned by lineages, and individual trees within each grove were owned by families within a lineage. The harvest season for acorns was from October to November, occurring just prior to or at the beginning of the first winter rains. If it rained before a crop could be harvested, acorns on the ground became wet and turned black. All these acorns were said to taste different and were considered unfit for consumption, however, they were eaten in periods of food shortage. When the acorns were ripe for harvesting, hunters or others who had visited the oak groves notified the lineage leader who then informed his people. A small gathering of acorns was made and these then processed either at the oak grove or in the ceremonial house of the lineage. It was understood that sickness or death would be visited on anyone who gathered acorns before this ceremony. During the harvest, most of the men, women, and children in a village moved to the oak groves. This trip took anywhere from one to two days to make. Customarily, the gatherers remained for three to four weeks camped in the oak groves to permit the acorns to dry. The men climbed the oak trees and knocked acorns to the ground, while the woman and children gathered up these acorns and those that had fallen naturally. The husks of the acorns were cracked by placing each acorn on a flat rock with a small indentation and striking it with a smaller rock. The acorns were then laid out for drying. During the weeks in which the acorns were being gathered, dried, and processed, the men also hunted deer and an abundance of small game. Fresh acorns have a bitter, astringent taste, caused by the presence of tannic acid. All acorns therefore required leaching before they could be used as food. According to Cahuilla oral literature, acorns were not always bitter. One version of the story says that the creator-god Mukat became angry at his people and turned acorns bitter. Each Cahuilla woman had her own gathering and processing equipment. The principal implements were carrying baskets, the mortar, the pestle, leaching baskets, sifting baskets, used to separate coarse meal from fine meal, a spoon, and a small hand broom which was used to clean mortars after grinding. Mortars were made by heating the area to be ground out and chipping it with a sharp rock. The depression was then further ground out with a pestle. The significance attached to ownership of mortars was such that after a woman died her mortar was broken and buried upside down. After acorns were ground, the meal was the placed in a loosely woven leaching basket or an indentation in the sand. A layer of grass leaves, or other fibrous material served as a lining at the bottom of the basket to prevent loss of the meal. Warm or cold water was poured through the meal several times until the tannic acid was removed. Two grades of ground acorn meal were prepared. A fine meal was used in making acorn bread, which was a meal cake baked on hot coals for several hours. With the introduction of the Mexican tortilla, acorn bread was discontinued among the Cahuilla in favor of the tortilla. Coarse meal was used in making acorn mush. This meal swells to twice its amount during cooking and turns pale pink or tan color. The cooking process was a delicate one since mush that failed to attain the proper consistency hardened when cold. Acorn mush jells into a firm consistency like a custard when properly cooked. It can be cut into squares and eaten or eaten directly from a vessel. The acorns which were not ground and processed in the oak groves, were carried back to the village and stored in granaries. Because these cylindrical granaries were woven from pliable plant materials, air freely circulated through the acorns. The granaries were placed in trees or on posts to prevent rodents from getting into them. Acorns could be stored for a year or more in such granaries. Acorn meal was also preserved by forming it into cakes and allowing them to dry. The cakes could be stored for a long period, then reground and recooked. A narrow necked olla was customarily used in storing ground meal, which had a flat rock as a cover to keep out pests. Such pottery was made from red clay. These storage jars were hidden in dry caves and clefts of rock to ensure an emergency food supply. Acorns were also used in trade activity that accompanied ceremonial occasions. The Cahuilla of San Gorgonio Pass, for example, regularly traded with the Serrano people to the north and the desert Cahuilla groups. Acorn meal was exchanged frequently for pinyon nuts with the Serrano and for mesquite beans and palm tree fruit with the desert Cahuilla. Acorn meal was also used as a payment for special services. If a Cahuilla was treated for an illness by a shaman, he might pay him with acorn meal. (Bean & Saubel 121). There are few mammals or birds that can ingest acorns due to the high tannin content, the mammals that can are the Brush Mouse, the Dusky-footed Wood Rat, the California Ground Squirrel and the Pocket Gopher. Birds that have built up a tolerance for tannin are: the Scrub Jay, the Band-tail Pigeon, the California Quail and the Acorn Woodpecker. (Native plant class taught by Dave Bontrager through Coastline Community College, spring 1985). For an external wash and dressing, the bark of the oak is collected in the early spring or late fall when the tannin is the highest; the galls of the twigs when they are still flecked with red and moist, the leaves in early fall. In small oaks, the stems are used. A tea of the bark can be used with success as a wash for gum inflammations, as a gargle for sore throats, as an intestinal tonic, and for diarrhea. The active ingredients are tannin and quercin, the latter with similar effects to salicin. Although somewhat outmoded in clinical practice, tannin is still a useful treatment for first and second degree burns, acting as a binder with the proteins and amino acids of the weeping, burned tissue and rendering them more impervious to bacterial action. All parts of the Oak are similarly useful as a first aid in inflammations, abrasions, and cuts, having a clotting, shrinking, and antiseptic effect. Oak should be placed first on any list of native remedies for hikers and back packers. It is common, easily identifiable, easy to use, and effective for most of the potential problems faced in the wilderness. The leaves can be chewed into a bolus and applied to insect bites to reduce the swelling, and a piece of the bark can be chewed to lessen the pain from a minor toothache. The galls are growths found along the twigs of many Oaks, most frequently the evergreen varieties. Certain wasps lay their eggs in the twigs, and the larvae secrete an enzyme that causes the plant to form "Oak Apples" around them. These galls contain two or three times the tannin of the bark and are especially useful, fresh or dried, and an external wash and dressing. The quercin contained in the bark makes it a useful adjunct to bioflavenid (Vitamin P) therapy for reducing capillary fragility. (Moore, Medicinal Plants of the Mountain West 116). Oaks, particularly, Quercus agrifolia and Q. lobata, yielded acorns which were unquestionably the most important staple food of the Chumash, Indians of the Channel Islands, the nearby coast and adjacent mountains. Their value was due both to abundance and to storability. (Timbrook, J. "Chumash Ethnobotany: A preliminary Report". Journal of Ethnobiology. December 1984, 141-169). Native Americans would gather 500 pounds per family, which was a year's supply. (Hutchens 147). The leaves and buds have been known to poison livestock, therefore humans should be wary of eating them. (James 54).

Text Ref:

Hickman, Ed. 660; Munz, Flora So.

Calif. 479; Roberts, The Oaks of So.

Calif. Floristic Province 29.

Photo Ref:

Jan-Mar 96 # 6,7; May 96 # 3A.

Identity: by R. De Ruff, confirmed by John Johnson.

First Found: February 1996.

Computer Ref: Plant Data 495.

Have plant specimen.

Last edit. 12/20/04.

|

|

February Photo May Photo